Protocol Oriented Programming in Swift

What’s POP, Why Should You Use It, How Does it Work in Reality? Protocol-Oriented Programming is a new programming paradigm ushered in by Swift 2.0. Check out this guide to learn more about the protocol-oriented approach today!

Jan 10, 2019 • 13 Minute Read

Introduction

What’s POP, Why Should You Use It, How Does it Work in Reality?

Swift - the First POP Language

At WWDC 2015, Apple announced that Swift is the world’s first Protocol-Oriented Programming (POP) language.

So What’s POP?

Protocol-Oriented Programming is a new programming paradigm ushered in by Swift 2.0. In the Protocol-Oriented approach, we start designing our system by defining protocols. We rely on new concepts: protocol extensions, protocol inheritance, and protocol compositions. The paradigm also changes how we view semantics. In Swift, value types are preferred over classes. However, object-oriented concepts don’t work well with structs and enums: a struct cannot inherit from another struct, neither can an enum inherit from another enum. So inheritancefa - one of the fundamental object-oriented concepts - cannot be applied to value types. On the other hand, value types can inherit from protocols, even multiple protocols. Thus, with POP, value types have become first class citizens in Swift.

Start with a Protocol

When designing a software system, we try to identify the elements needed to satisfy the requirements of a given system. We then model the relationships between these elements. We can start with a superclass and model its relationships through inheritance. Or we can start with a protocol and model the relationship as a protocol implementation. Swift provides full support for both interpretations. However, Apple tells us:

“Don’t start with a class, start with a protocol.”

Why? Protocols serve as better abstractions than classes.

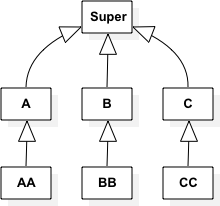

If you model an abstraction using classes, you’ll need to rely on inheritance. The superclass defines the core functionality and exposes it to subclasses. A subclass can completely override that behavior, add specific behavior, or get all the work done by the superclass. This works nicely until you realize that you need more functionality from a different class. Swift, just like many other programming languages, does not support multiple inheritance. Following the class-first approach, you’d have to keep adding new functionality to your superclass or otherwise create new intermediary classes, thereby complicating the issue. Protocols, on the other hand, serve as blueprints rather than parents. A protocol models abstraction by describing what the implementation types shall implement. Let’s take for example the following protocol:

protocol Entity {

var name: String {get set}

static func uid() -> String

}

What it tells us is that adopters of this protocol will be able to create an entity, assign it a name and generate its unique identifier by implementing the type method uid().

One type can model multiple abstractions, since any type - including value types - can implement multiple protocols. This is a huge benefit over class inheritance. You can separate the concerns by creating as many protocols and protocol extensions as needed. Say good-bye to monolithic superclasses! The only caveat is that protocols define a template abstractly -- with no implementation. Here’s where protocol extensions come to the rescue.

The Pillars of POP

Protocol Extensions

Protocols serve as blueprints: they tell us what adopters shall implement, but you can’t provide implementation within a protocol. What if we need to define default behavior for conforming types? We need to implement it in a base class, right? Wrong! Having to rely on a base class for default implementation would eclipse the benefits of protocols. Besides, that would not work for value types. Luckily, there is another way: protocol extensions are the way to go! In Swift, you can extend a protocol and provide default implementation for methods, computed properties, subscripts and convenience initializers. In the following example, I provided default implementation for the type method uid().

extension Entity {

static func uid() -> String {

return UUID().uuidString

}

}

Now types that adopt the protocol need not implement the uid() method anymore.

struct Order: Entity {

var name: String

let uid: String = Order.uid()

}

let order = Order(name: "My Order")

print(order.uid)

// 4812B485-3965-443B-A76D-72986B0A4FF4

Protocol Inheritance

A protocol can inherit from other protocols and then add further requirements on top of the requirements it inherits. In the following example, the protocol Persistable inherits from the Entity protocol I introduced earlier. It adds the requirement to save an entity to file and load it based on its unique identifier.

protocol Persistable: Entity {

func write(instance: Entity, to filePath: String)

init?(by uid: String)

}

The types that adopt the Persistable protocol must satisfy the requirements defined in both the Entity and the Persistable protocol.

If your type requires persistence capabilities, it should implement the Persistable protocol.

struct PersistableEntity: Persistable {

var name: String

func write(instance: Entity, to filePath: String) { // ...

}

init?(by uid: String) {

// try to load from the filesystem based on id

}

}

Whereas types that do not need to be persisted shall only implement the Entity protocol:

struct InMemoryEntity: Entity {

var name: String

}

Protocol inheritance is a powerful feature which allows for more granular and flexible designs.

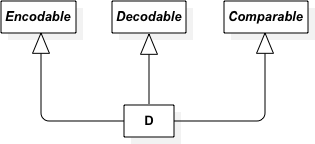

Protocol Composition

Swift does not allow multiple inheritance for classes. However, Swift types can adopt multiple protocols. Sometimes you may find this feature useful.

Here’s an example: let’s assume that we need a type which represents an Entity.

We also need to compare instances of given type. And we want to provide a custom description, too.

We have three protocols which define the mentioned requirements:

- Entity

- Equatable

- CustomStringConvertible

If these were base classes, we’d have to merge the functionality into one superclass; however, with POP and protocol composition, the solution becomes:

struct MyEntity: Entity, Equatable, CustomStringConvertible {

var name: String

// Equatable

public static func ==(lhs: MyEntity, rhs: MyEntity) -> Bool {

return lhs.name == rhs.name

}

// CustomStringConvertible

public var description: String {

return "MyEntity: \(name)"

}

}

let entity1 = MyEntity(name: "42")

print(entity1)

let entity2 = MyEntity(name: "42")

assert(entity1 == entity2, "Entities shall be equal")

This design not only is more flexible than squeezing all the required functionality into a monolithic base class but also works for value types.

A Cleaner Design with POP

I’ll walk you through an example which shows the benefits of Protocol-Oriented Programming over the classical approach.

Our aim is to create types which fulfill the following requirements:

- Create an image given a name and image data

- The image should be persisted to and loaded from the filesystem

- Create a lossy compressed version of the image

- Base64 encode the image for transferring it over the internet

The Superclass Way

Let’s start with the base class approach. I squeeze all the features in the Image class. What we get is a complete type: we can create instances of the Image class directly, and we get all the requirements fulfilled.

class Image {

fileprivate var imageName: String

fileprivate var imageData: Data

var name: String {

return imageName

}

init(name: String, data: Data) {

imageName = name

imageData = data

}

// persistence

func save(to url: URL) throws {

try self.imageData.write(to: url)

}

convenience init(name: String, contentsOf url: URL) throws {

let data = try Data(contentsOf: url)

self.init(name: name, data: data)

}

// compression

convenience init?(named name: String, data: Data, compressionQuality: Double) {

guard let image = UIImage.init(data: data) else { return nil }

guard let jpegData = UIImageJPEGRepresentation(image, CGFloat(compressionQuality)) else { return nil }

self.init(name: name, data: jpegData)

}

// BASE64 encoding

var base64Encoded: String {

return imageData.base64EncodedString()

}

}

// Test

var image = Image(name: "Pic", data: Data(repeating: 0, count: 100))

print(image.base64Encoded)

do {

// persist image

let documentDirectory = try FileManager.default.url(for: .documentDirectory, in: .userDomainMask, appropriateFor:nil, create:false)

let imageURL = documentDirectory.appendingPathComponent("MyImage")

try image.save(to: imageURL)

print("Image saved successfully to path \(imageURL)")

// load image from persistence

let storedImage = try Image.init(name: "MyRestoredImage", contentsOf: imageURL)

print("Image loaded successfully from path \(imageURL)")

} catch {

print(error)

}

Now, what if we don’t need all these features? Let’s say I don’t always need the Base64 encoding functionality. If I subclass the Image class, I’ll get all the features - even if I don’t need them.

If we need to create subclasses to specialize some of the methods, there is no way to get rid of those public methods and properties we don’t need. We just get everything when we inherit.

Besides, we are constrained to classes only. Now, let’s revamp this design using POP.

Redesign using POP

I’ll create protocols for each major feature, that is persistence, creation of a compressed, lossy version and Base64 encoding.

protocol NamedImageData {

var name: String { get }

var data: Data { get }

init(name: String, data: Data)

}

protocol ImageDataPersisting: NamedImageData {

init(name: String, contentsOf url: URL) throws

func save(to url: URL) throws

}

extension ImageDataPersisting {

init(name: String, contentsOf url: URL) throws {

let data = try Data(contentsOf: url)

self.init(name: name, data: data)

}

func save(to url: URL) throws {

try self.data.write(to: url)

}

}

protocol ImageDataCompressing: NamedImageData {

func compress(withQuality compressionQuality: Double) -> Self?

}

extension ImageDataCompressing {

func compress(withQuality compressionQuality: Double) -> Self? {

guard let uiImage = UIImage.init(data: self.data) else {

return nil

}

guard let jpegData = UIImageJPEGRepresentation(uiImage, CGFloat(compressionQuality)) else {

return nil

}

return Self(name: self.name, data: jpegData)

}

}

protocol ImageDataEncoding: NamedImageData {

var base64Encoded: String { get }

}

extension ImageDataEncoding {

var base64Encoded: String {

return self.data.base64EncodedString()

}

}

With this approach we can create more granular designs. You can create a type which adopts all the protocols:

struct MyImage: ImageDataPersisting, ImageDataCompressing, ImageDataEncoding {

var name: String

var data: Data

}

Or you may decide to skip the conformance to ImageDataPersisting:

struct InMemoryImage: NamedImageData, ImageDataCompressing, ImageDataEncoding {

var name: String

var data: Data

}

The bottom line is that you can choose which protocol to adopt in your types. And your types can be references or value types. This flexibility does not exist if the implementation is done with superclasses.

Another benefit is that we can provide default implementations with protocol extensions. Actually, we could even add new functionality - and here’s the best part: we don’t even need the original code. We can extend any Foundation or UIKit protocol and decorate it according to our needs without delving into class structure or other nitty gritty details.

Final Thoughts

Swift supports multiple paradigms: Object-Oriented Programming, Protocol Oriented Programming and Functional Programming. What does this mean to us, software developers? The answer is FREEDOM.

It’s up to you which paradigm to choose. You can still go the OOP-route if you wish. You could mix and match. However, once you wrap your head around Protocol-Oriented Programming, you’ll probably never look back.

Check out my Swift courses on Pluralsight.

Thanks and Happy Coding!

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Marshall Elfstrand, Swift & Developer Tools Evangelist at Apple, for his valuable suggestions.

Advance your tech skills today

Access courses on AI, cloud, data, security, and more—all led by industry experts.